I love compressors and compression and how it can make or break a track. I like how it takes finesse to do, that aspect appeals to me. But there is one thing I don't fully understand. Attack time. Release is easy enough to understand. Set it so that it releases gradually enough that you don't hear it, but not so long that it's like a clingy girlfriend. I just hope someone can explain the theory behind attack, because I can't think of one, certainly not one larger than 10ms.

Comments

You'd think the look ahead feature would be something that you a

You'd think the look ahead feature would be something that you always want? Believe me, it isn't. In fact, in software, I frequently disable look ahead. Because I want that peak slammin' through while it then brings up the rest of the tone. So slower attacks = more apparent dynamic punch while the volume is being controlled.

Faster attacks are better on vocalists. The human voice is really difficult to record well. It's more than just a microphone & preamp. Most vocal dynamics sound unrealistic when recorded. So we make them more realistic sounding by removing the realism with dynamics processing. Than it sounds more real and sits in the mix, where it's supposed to. Otherwise we beat it into submission and slap it upside of the meter, with a limiter. Yeah baby! Tame that bad boy or girl.

I'll never be tame. Nor can I be housebroken.

Ms. Remy Ann David

Haha, nice post Remy. That's more what I was looking for, the p

Haha, nice post Remy. That's more what I was looking for, the practical uses of that particular knob, if that makes sense. Just for reference, what ranges are considered "fast" or "slow" because I usually don't go above 10ms for anything. But then again with my humble recording background I have never really had to.

read 'Dune'. if Usul wants to penetrate the shield in a knife fi

read 'Dune'. if Usul wants to penetrate the shield in a knife fight, the attack needs to quick enough to not be parried, and slow enough so the knife point penetrates the shield and is not deflected.

call me a geek, but i think i've read that book about 20 times; very informative for audio.

Perhaps I'm misguided, perhaps some compressors work this way an

Perhaps I'm misguided, perhaps some compressors work this way and others don't, but...

Does the attack not "ramp up" the compression - over the course of that 10ms it gradually applies with greater reduction?

At 0ms it's off. At 5ms it's reducing by 50% of the ratio. At 10ms it's reducing by the full ratio. Meaning that your transients will still escape but slightly less.

I imagine this would be easier with audio demonstrations and a 300ms attack time.

It follows that my interpretation of pre-comp is the amount of time before it starts to follow the attack curve.

Look-ahead would be a way of having the detector circuit work with the signal volume from X ms beforehand (by delaying the signal input for example).

Codemonkey wrote: Perhaps I'm misguided, perhaps some compressor

Codemonkey wrote: Perhaps I'm misguided, perhaps some compressors work this way and others don't, but...

Does the attack not "ramp up" the compression - over the course of that 10ms it gradually applies with greater reduction?

At 0ms it's off. At 5ms it's reducing by 50% of the ratio. At 10ms it's reducing by the full ratio. Meaning that your transients will still escape but slightly less.

BZZZZZZZZT!! WRONG... thanks for playing!

You are confuzzling attack over threshold...

Attack at 0mS could be 400% of the ratio... just as it could be 400% below ratio.... depending upon the threshold.

Which brings up knee... and how hard you slam that gain makeup.

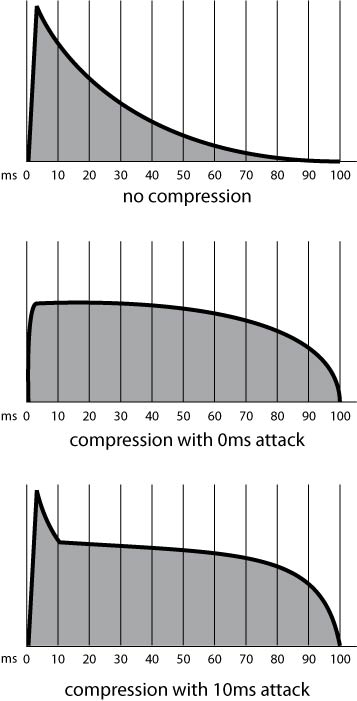

If you want to hear how attack works, put some kind of sound wit

If you want to hear how attack works, put some kind of sound with a sharp transient and some kind of decay....like a snare drum, and play with the knob. My analogy for a compressor is its like a monkey thats trained to turn down a volume knob. The attack knob is telling the monkey how long to wait before he turns the volume down. With an attack of 0, the snare is going to have the normal ratio of attack (transient) vs decay. As the attack gets longer, that initial peak gets louder in comparison to the decay...making it pop.

Try it with an organ sound too...something that has constant volume. As you increase the attack, you'll be manufacturing a small peak at the front of the signal.

Of course, none of this does anything if your signal isn't exceeding the threshold of the comp.

These things are a lot easier to understand if you have an idea of what it does first, and then try it out on some different sources to see what that means in the real world.

With an attack of 0, the snare is going to have the normal ratio

With an attack of 0, the snare is going to have the normal ratio of attack (transient) vs decay. As the attack gets longer, that initial peak gets louder in comparison to the decay...making it pop.

Thanks, I like all this info, but I'm still a bit unclear. I will try to re-phrase my question based on the example of the snare drum. There are two (maybe more) aspects of a snare drum hit. But two that I am concerned about. The attack, and the reverberation. If you tell the compressor to wait until after the initial attack of the snare, the main sound of the instrument, then you are really only compressing the reverberation. Then in this case, aren't you using a compressor much like you would a noise gate? Then what is the point of using the compressor in the first place?

the compressor adds density to your signal as it evens out the t

the compressor adds density to your signal as it evens out the the loud and the low parts of it.

for example, when you have a vocal track it brings down the loud parts and brings up the low parts so you'll have a more consistent level. if you don't use a compressor your singer will stand out of your mix when singing loud and go under when singing quietly.

a noise gate just mutes the part of the signal that's below your set threshold.

the attack setting on a compressor is just a tool to prevent the initial peak (attack) of the signal to be brought down so it won't lose the punch.

MadMax, I wasn't referring to that... I know what a Threshold do

MadMax, I wasn't referring to that... I know what a Threshold does, surprisingly.

What I should've made clear was that my impression is that the >>reduction which is being applied to the signal<< in relation to the ratio control is ramped up.

The amount of reduction at the point of crossing the threshold is 0dB - after 5ms (10ms attack) it is reducing the amount which would be reduced if the ratio were set to half of it's actual value and at 10ms the reduction is the full amount it should be reduced by.

Still wrong? This is sounding somewhat like a knee control now although my impression of those was that it ramped the input volume to the detector circuit.

*codemunkeh has left the chat (shamed and confused).

Try this... Go to a snare track in your DAW and zoom in on the

Try this...

Go to a snare track in your DAW and zoom in on the wave-form. You'll see the transient...the big blob with a quick rise and then fall, and then the decay, which should slowly fall off in a linear manner.

You are right, there are two parts. When you are setting the attack on a snare drum, you are choosing how much of that first blob, that pop sound, comes through before the compressor grabs the signal and drops it down.

If you set your attack too long, so that it was the entire length of that first blob, your compressor wouldn't really do anything, because after the attack length, the trail would be under the threshhold. You'd be effectively turning the compressor off.

If you want the compressor to do its thing, then, you need to set your attack so that just the beginning of that blob is let through before getting turned down. How this sounds is hard to explain, its best to try it out. A bass guitar might be a better example, because there is an initial transient as the finger or pick hits the string, and then a decay of similar level. If you want to reduce the volume of that initial transient, you would lower the attack time. If you want those transients to pop through, and then have the compressor grab it and turn it down, you would increase the attack time.

You could try this: record a single snare drum hit at a normal

You could try this: record a single snare drum hit at a normal dynamic level, then copy and paste that about 5 times, loop that track, and then play with the compressor so you can hear what it's actually doing. People can explain things to you all day, but until you actually start figuring out for yourself what the compressor is really doing you won't really get anywhere.

the attack defines when the compression takes effect. if you set

the attack defines when the compression takes effect.

if you set the attack to 0 it compresses the signal including it's very first transients (attack of a signal) immediately. this setting, applied for example to a snare drum, will make the drum sound somehow softer and rather undefined, because the attack of the drum hit is reduced in relation to the sustain.

if you set the attack on the compressor to a value higher than 0 it will let the beginning of the sound (transient) pass without compression for the set amount of time (e.g. 30ms -> the first 30 ms of the sound will not be compressed). this leads to a more punchy sound, because the attack of the hit is increased in relation to the sustain.

for more information and if you didn't understand a word i said (which wouldn't surprise me, given that i'm not a native english speaker) you can check also the following link

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dynamic_range_compression#Attack_and_release

by the way, a hardware compressor will never achieve 100% accurate 0ms attack due to the slower response of analog technology. many plugin compressors have a lookahead function, which detects oncoming signals, so that it knows exactly when to start processing.

hope this helps! :?